Waste incineration and the UK Emissions Trading Scheme

As an environmental engineer for over 20 years, I have fought a long and largely unsuccessful battle to reduce waste in the construction sector. Then, in recent years, fighting the construction of a massive new incinerator near my home in Edmonton, North London, I began to research municipal waste and found that there has been a startling increase in waste incineration over recent years. Investigation lead to the realisation that the economics of waste are fundamentally stacked against reduction and circularity.

Since the introduction of the landfill tax in 1996, waste sent to landfill in the UK has declined from over 90% in 1993 to less than 10% today. It has been a brilliantly successful fiscal instrument. In the 10 years from 2000, average recycling rates across the UK increased from 10% to 40% while incineration rates remained largely static. Then, around 2010, things changed. While landfill continued to decline and recycling languished at 40%, incineration rates rose sharply from 15% in 2010 to over 45% today and rising quickly.

In the last 3 years, average recycling and composting rates have also started to fall, despite the fact that the proportion of recyclable plastic, fabric and packaging in our bins has greatly increased. For all the talk of a circular economy, the reality is slipping ever further away.

As I write, there are 48 operational municipal waste incinerators in the UK with 17 under construction. Last year, these incinerators created 6.7Mt CO2 – that’s the same as all the homes, offices, transport & industry in Manchester and Birmingham put together. Then consider that, based on the number of incinerators currently seeking planning, UK incineration capacity will double in the next few years.

We are in the grip of incineration insanity. But why?

It won’t surprise you to hear that companies don’t make money from waste reduction, but there is plenty of profit from incineration. Unlike landfill, incineration operators pay no tax either as a waste disposal route or as a major CO2 emitter, unlike other fossil fuel power stations burning coal or gas. There are no carbon emissions targets or requirements to reduce CO2 emissions over time.

In the UK, all businesses and public services like schools must pay an additional fee for collection of dry mixed recycling and most households pay extra for collection of green waste. In addition, those living in local authority flats do not always have recycling bins. Recycling rules differ across county lines and there is little education on waste and no penalties for failing to segregate. The lack of incineration tax and the ability of EfW operators to be paid both for the “fuel” they burn and the energy they produce allows them to undercut recycling and offer cheap disposal to businesses and local authorities. So when times are tough, recycling gets cut.

The polluter pays principle clearly isn’t working here, so I started investigating mechanisms for bringing this balance back into check. I didn’t have to look far.

As a result of Brexit, the UK government must rewrite many environmental policies. On 1st June 2020, “The Future of UK Carbon Pricing” was released by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and industrial Strategy. It set out the UK government’s response to a consultation conducted two years earlier on carbon taxation. Unsurprisingly, they decided to continue the EU’s carbon emissions trading scheme mechanism.

Due to start in January 2021, the new UK ETS includes aviation, manufacturing and fossil fuel power generation but, despite being major CO2 emitters enjoying enormous growth, municipal and hazardous waste incinerators are excluded from the scheme.

This leaves incinerators operating in the shadows, applying creative carbon accounting practices to report their emissions, pouring out CO2 at will with no “carrot or stick” in place to reduce greenhouse gases.

The Committee on Climate Change, advisers to the UK government on carbon policy, has recommended that, in order to meet our Paris Agreement commitments and keep CO2 emissions well below the 2degC global warming target, carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology must be installed on waste incinerators at some point in future. Sounds reasonable, yet there exists no technology available at scale that is capable of removing CO2 emissions from incineration exhausts. A single pilot was undertaken in Norway this year, but the equipment is hugely expensive and a long way from wide scale roll-out. And without carbon targets or taxation there is no incentive to invest in this experimental technology.

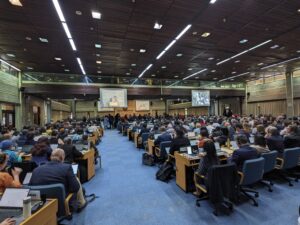

And so, on 1st September 2020, my legal team filed papers in the High Court, challenging the UK government over the failure of the UK Emissions Trading Scheme to uphold our Paris Agreement commitments.

My case centres around three central grounds:

- That the government acted unlawfully and disregarded the Paris Agreement by excluding waste incineration from the UK ETS.

- That by providing far too many CO2 allowances (well above “business as usual” emissions), they are unlawfully failing to reduce industrial CO2 quickly enough.

- That the reason given for setting the emissions ceiling so high is unlawful, i.e. to maintain industrial competitiveness and soften the blow of Brexit. This is contrary to the Paris Agreement.

Our public hearing is on 1st December when the High Court will give permission to proceed. If permitted, the court date will be set for some point in the following weeks. I am represented by Leigh Day solicitors and David Wolf QC who successfully challenged the Heathrow expansion earlier this year, also on the basis of the Paris accord. I am crowdfunding for the legal fees through CrowdJustice and response from the public has been overwhelming.

By including incinerator operators in the UK ETS, they will be forced into a regime where emissions are accurately reported, managed, taxed and reduced over time. The economics will promote investment in alternatives such as recycling and reuse, investment in carbon capture and storage technology and, ideally, create a case for waste reduction.

About the author

Georgia Elliott-Smith is an environmental engineer and Managing Director of sustainability consultancy, Element 4 Group Ltd (element-4.co.uk), worked with corporates and public sector organisations for over 20 years to improve environmental and social impacts.

As an environmental activist and UNESCO Special Envoy for Youth and the Environment, she is currently engaged in a legal challenge of the UK government over failure of the proposed UK ETS to uphold the Paris Agreement.