Living better, living waste free

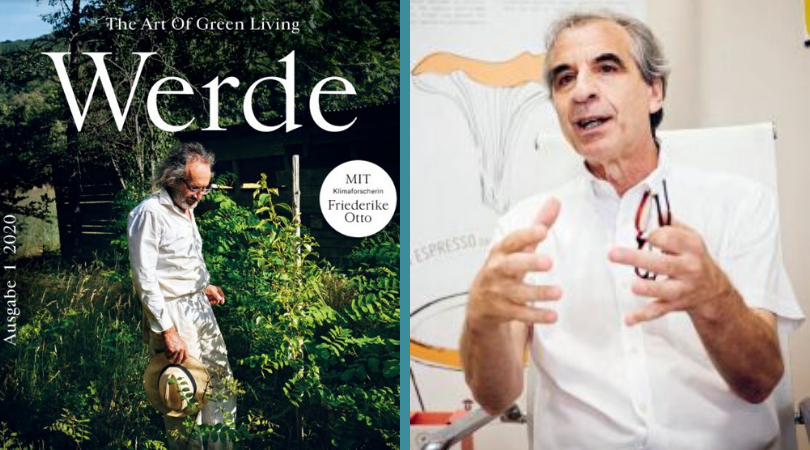

This article was published in German by the journal WERDE in January 2020.

Rossano Ercolini is a teacher and an activist. He advises European cities on recycling and waste. In Naples waste separation is getting successful, and in Paris a whole quarter counts on composting.

Rossano Ercolini bends down and reaches for a crumpled plastic bottle, which somebody threw away in the town hall square in Capannori, a town in Tuscany with 50,000 inhabitants.

The man in his mid-60s is not a pensioner who boosts his budget with discarded plastic bottles. (In Germany a lot of people do so.) But it is Ercolini’s heart’s desire to recycle garbage. For more than twenty years, he has been getting people to participate: It’s because of him that the population of around 300 Italian municipalities presorts 80 to 95% of their household waste for recycling. To compare: the German average is at about 65%. But not only that: due to his work the separation of waste has become a good practice throughout Europe.

In a café opposite the town hall, the Italian puts the plastic bottle he found on a little table. “This bottle is a valuable resource”, he looks straight into his interviewer`s eyes and raises his brows.

“If we collect disposed glass, cardboard, plastic and organic waste separately, we can continue to use them. But when we throw it away altogether, we create waste.” Everyone understands these equations. Ercolini is a primary school teacher. He never tires of explaining that the disposal of waste causes greenhouse gas emissions and wastes resources, which are getting scarcer and scarcer.

Ercolini’s commitment is a success story that began with a protest action in 1996. The regional government of the Province of Lucca was planning the construction of two waste incineration plants. “I wanted to prevent this because I feared for the health of my students”, says the activist, carefully sipping his Espresso. “One of the facilities was to be located near the school.” He succeeded in making the public aware of the risks of the incineration plant and convinced the people. The government withdrew its plans. The incinerator was not built.

Where to put the garbage?

Even as a zero waster, Ercolini cannot get rid of his plastic bottle. In a residential neighbourhood near the café Daniele Pellegrini does not collect plastic this day, but glass. He drives the little garbage truck himself, which is operated with natural gas in an environmentally friendly manner. Pellegrini lifts the lid of a garbage can. “When I realize that the bottles and glasses are not clean, or when there is residual waste or plastic in the bin, I don’t take the garbage away.” He sticks an inscription on it with the words: Attention: this material is not properly separated. “But that does not occur very often,” he says.

“The cleaner the plastic, paper or glass, the better the quality of the recyclate,” explains Ercolini. “Pizza boxes, for example, are rather residual waste, because they are usually very greasy.” From the beginning, the people of Capannori took waste separation seriously. “They appreciated that we didn’t just say no,” recalls the zero waste pioneer, “we were also delivering alternatives to waste incineration.” And these alternatives started with the reduction of the residual waste. Even in the few apartment blocks of Capannori there are no more general containers, instead each housing unit places its own bags and bins on the street. “People feel more responsible about their waste and they sort better,” says Ercolini, who introduced this system as an interim manager of the public garbage collection. For this task he had to take a year’s leave of absence as a primary school teacher. “It is mainly this collection system that contributes to being able to recycle so much waste,” he reports. “We sell our recyclable waste, plastic, aluminium, iron, steel, for 140 EUR per tonne to the national packaging consortium, that recycles a large percentage.” But also plastic consumed in Capannori is sometimes burned in order to produce energy. “Plastic is our big problem,” says Ercolini. “Our goal is to recycle more plastics, anything else is just a temporary solution.” Paper recycling works much better: The paper mills of the surrounding areas are using a large amount of the paper-waste produced.

Reception with Barak Obama?

A second important measure: Ercolini carries out random samplings of residual waste bins. He calls it “screening”(residual waste audit). He finds lots of nappies in the bins. Although the city government supports the purchase of cloth diapers, in Capannori most parents use disposable nappies to change their babies. But Ercolini has already contacted the world’s first diaper recycling plant in the northern Italian city of Treviso. During the school holidays, if he is not teaching, Ercolini has been advising other communities, he was also consulting in Istanbul and Beirut. His expertise is even demanded in Naples: for decades the Camorra together with corrupt politicians prevented a correct functioning of the waste management system. If the garbage piled up on sidewalks and streets, the clans picked it up for horrendous prices to cart it off to illegal landfills. But with Ercolini’s support, bit by bit, more waste separation is succeeding. “I have no wife and no children,” he says with his broad smile, “and can almost invest my whole time.” For his commitment, the Italian was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2013, a renowned Environmental Protection Award. In this context a reception with then US President Barack Obama took place. “We should dress formally,” says Ercolini, who stands up straight and makes a serious face. “I was wearing a suit and tie when Obama shook my hand.” It is clear to see that Ercolini was very glad about the recognition. But the fact that trousers and jackets do not contain plastic is more important for him than the dress code, because it escapes in microparticles during washing and ends up in the treated wastewater in rivers and lakes.

For his commitment, the Italian was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2013, a renowned Environmental Protection Award. In this context a reception with then US President Barack Obama took place. “We should dress formally,” says Ercolini, who stands up straight and makes a serious face. “I was wearing a suit and tie when Obama shook my hand.” It is clear to see that Ercolini was very glad about the recognition. But the fact that trousers and jackets do not contain plastic is more important for him than the dress code, because it escapes in microparticles during washing and ends up in the treated wastewater in rivers and lakes.

Following Ercolini’s work, the city council of Capannori signed in 2007 the zero-waste strategy and thus committed itself to standards like a consistent waste sorting system, as the first city in Europe. With the city of Kiel, which the Italian is currently supporting, the first German city is now working on a plan to join the zero waste initiative. Since the end of 2018, the movement is also advising on a project in Paris, in which about 6000 private persons and operators of more than 100 small businesses are working on the reduction of waste in the French capital. There is a lot of residual waste there. Almost 80% of all waste is residual waste. The Europe-wide average is 60%.

Léa Vasa, councillor of the 10th arrondissement, launched the Project “Rue Zero Déchet” with a bundle of measures for the Parisian district, as a local contribution to the national climate plan, which had already been declared by the French government in 2007. “For me it was important to respond to the wishes of local residents and draw from their experiences,” she said. “So the quarter was able to reduce its residual waste by 17% within a year.” People now sort their garbage more consistently. At the same time the amount of waste in the recycling bin also shrank. Overall, in the course of the last year, more than 100,000 kilograms of waste were completely avoided.

“Before, people used to call the City Hall because they wanted to complain about the garbage disposal that did not arrive on time”, says Vasa. “Now they call us, because they want to participate in our project.”

One of the first was Vittoria Romain with her restaurant Manicaretti in the Rue de Paradis. It’s 10.30 am on a weekday, she stands at the stove and cuts cauliflower stems small. What other cooks throw away, is transformed into delicious ingredients for the soup of the day. The bread from the previous day is served grilled and soaked in homemade almond milk to thicken a chocolate cream. “I only use leftovers where the nutrients are preserved and that taste good,” explains Romain. “Since the opening of my restaurant more than three years ago, I have followed a few rules about waste avoidance.” Her experience is now also being used by other restaurant operators. “I get fruit and vegetables in pallets made of wood and plastic, I give the packaging back to the suppliers to use them again.” In workshops, which the district administration offers within the project, Romain tells others about it. “I like to exchange experiences,” she says. “I realise that as a society we are moving.” She got her customers on board. From 12.30 pm onwards a lot of guests come to buy lunch. But many do not stay, they rather take their lunch to the office. “On average, 15 people bring their own reusable food boxes with them, and that number is rising,” observes Romain. “They get five% off.” If they take the big portion for 12 euros, waste avoiders save 60 cents a day.

Also Jean-Claude and Élodie Seguis, who live in the neighbourhood like workshops within the French project: they have learned to make deodorant and toothpaste themselves, and buy almost everything unpacked. And they pass on their own knowledge: in their typical Parisian kitchen with its clotheslines just below the ceiling to take advantage of that space too, Élodie Segui talks about a workshop where she set up a sewing machine and showed interested people on a weekend, how old pillowcases become environmentally friendly bread bags. But the whole pride of the couple is in the yard: a container with dozens of earthworms. They pull the vegetable and fruit waste from the inhabitants of the four-storey house deep into the container, eat them, digest and excrete out. This produces valuable compost. “To prevent it from becoming moist, we also add cardboard, which is best suited for egg cartons,” says Jean-Claude Seguis. “We talk with the other residents about the composter. Sometimes we meet next to the worms for an aperitif.”

Since winter 2018/19, when the project started, more and more residents are feeding earthworms with kitchen waste. “We have provided small composters, each can be used by one residential unit, free of charge,” explains Léa Vasa, the coordinator. “The households that participate, have reduced their residual waste by 20 to 30%” because biowaste has not been collected separately in the 10th arrondissement before. But there is more: “We have now extended our pilot project for a second year, especially to appeal to the many shopkeepers.” Vasa would like to contribute to the fact that in clothing stores more sustainable clothes will be offered and customers have the opportunity to return their old clothes.

Industry in the duty

Rossano Ercolini also knows that it is of great benefit if a city administration is involved: “In Capannori there are tax breaks for the operators of supermarkets, if they offer products unpackaged.” In his so-called Research Center, a hall where he presents the results of

research cooperations, he is chewing on a little tube which he conceived to replace both disposable straws and lollipops wrapped in plastic. “We have to force the industry. They have to withdraw certain products from the market such as coffee capsules, which cannot be recycled, and develop alternatives.” He wants to take the bottle home that he found in the town hall square in the morning in order to put it into his private container for plastic waste. He only has to have it emptied once a year.

Translation by Stephanie Eichler.

Read the article in German here.

Discover more about WERDE journal here or here.

Photo credit: @WERDE