At the EU level, urban biowaste, far from being managed by one set of straightforward policies, is instead held at the intersection of several competing mandates: the circular economy, climate, bioenergy and air pollution. Policies which have an impact, yet fail to drive the most sustainable use of this resource.

Most waste and circular economy policies aim at increasing recycling and resource efficiency of urban biowaste resources by promoting composting and biogas production, while climate and energy policies incentivize burning biowaste to generate energy under the assumption that the energy produced is ‘renewable’, ‘carbon neutral’ or ‘sustainable’. This presents a significant contradiction at the heart of EU environmental policy, one that gets particularly hot within the current sustainable bioenergy debate.

Far from being ‘sustainable’, energy from urban biowaste is often produced under very inappropriate circumstances, particularly when organic waste is mixed with the rest of residual waste (anything that cannot be recycled or reused) and sent to an incineration plant or so-called waste-to-energy plant. These plants then claim that the burning of this organic fraction is ‘bioenergy’ or ‘renewable energy’. In the UK, for example, incinerator companies can claim that an average of 50% of the energy produced is ‘renewable’ under these assumptions.[1]

Under the Waste Hierarchy, incineration of municipal solid waste is not only one of the worst options for waste treatment, it’s actually a real waste of energy and resources when one considers the low calorific value of organic waste. Incineration is a terribly unfit technology to burn organic waste which then requires a significant amount of high caloric materials to be added, e.g., plastics or other potentially recyclable or ‘redesignable’ materials so that it functions properly. Under these circumstances, efficiency and sustainability do not score highly. But even more troubling, the financial and political support that should be committed to clean, sustainable and reliable sources of energy is being misused in the most inefficient way by supporting the burning of resources which could be composted, recycled, reused or simply never wasted to begin with.

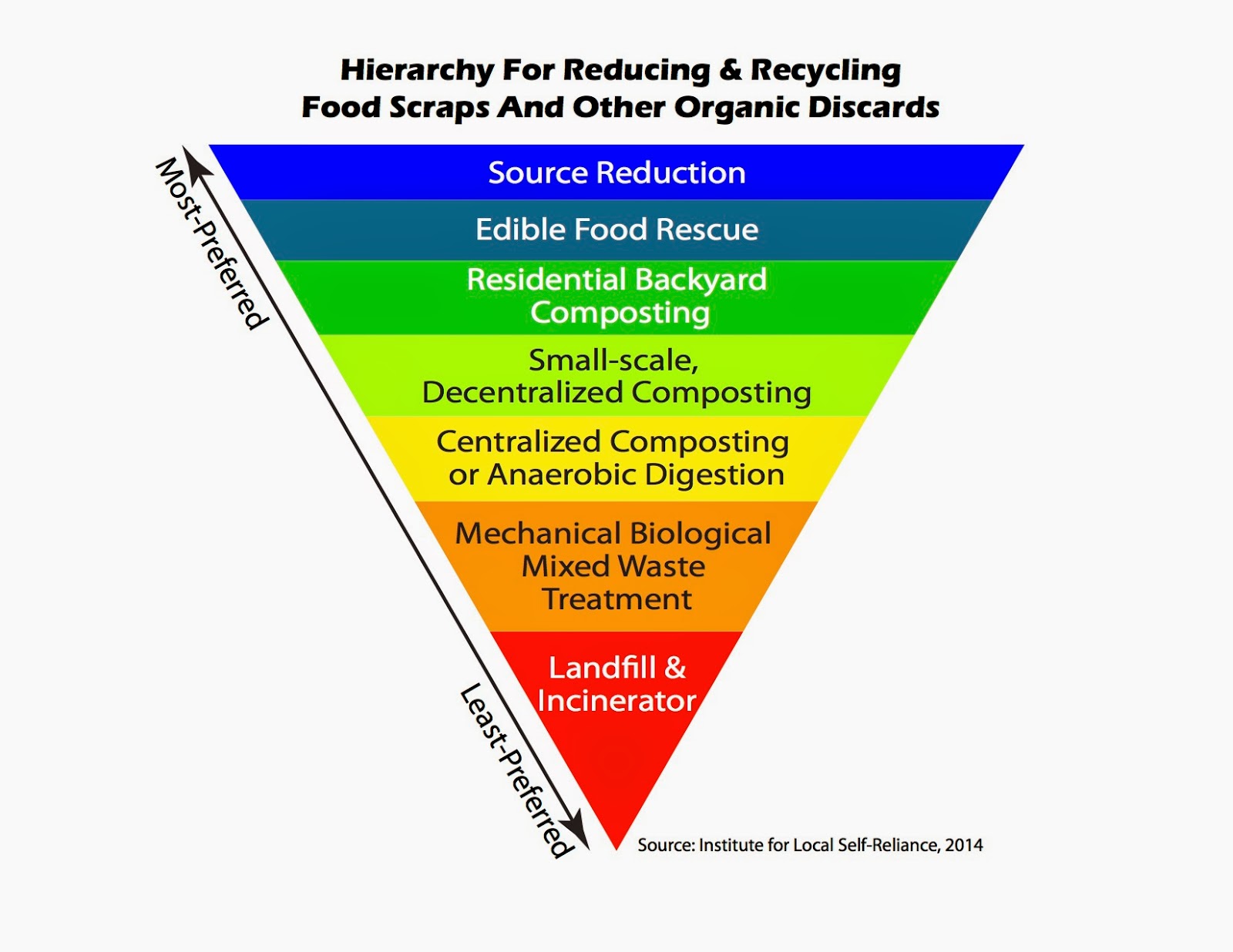

Today in the EU, harmful subsidies from renewable energy policies are one of the major obstacles to fully implementing a Circular Economy, because they continue to finance and green-wash the construction of waste-burning facilities across Europe. What should be done with urban biowaste instead? The Waste Hierarchy as seen below provides a clear detailed guideline which should be at the foundation of any policy looking at Municipal Solid Waste.

First, organic waste can be reduced through various measures, e.g., improved labelling, better portioning, awareness raising and educational campaigns around food waste and home composting. Secondly, priority should be given to the recovery of edible food so that it is targeted at human consumption first, and alternatively used as animal feed. Next, non-edible organic waste should be composted and used as fertiliser for agriculture, soil restoration and carbon sequestration. Additionally, garden trimmings, discarded food and food-soiled paper should be composted in low-tech small-scale process sites whenever possible. In larger areas, composting could be done in a centralised way with more technologically advanced systems.

As an alternative to composting, depending on local circumstances and the levels of nitrogen in the soils, non-edible organic waste should be used to produce biogas through Anaerobic Digestion technology, a truly renewable source of energy as well as soil enhancer. If there was any organic waste within the residual waste stream, a Material Recovery – Biological Treatment (MRBT) could be considered because it allows for the recovery of dry materials for further recycling and stabilizes the organic fraction prior to landfilling, with a composting-like process. In the lower tier, landfill and incineration are the least preferable and last resort options.

Ultimately, energy policies for a low-carbon economy should progressively move away from extracting as much energy as possible from waste and instead increase measures to preserve the embedded energy in products, a far more efficient and sustainable approach to resource use.

Zero Waste Europe network and many other organisations around the world have called on the European Commission to use the Waste Hierarchy to guide the EU’s post-2020 sustainable bioenergy policy and phase out harmful subsidies that support energy from waste incineration. The revision of the Renewable Energy Directive and the development of a Sustainable Policy on Bioenergy is an opportunity for Europe to become a leader in sustainable and renewable energy, but it’s critical to ensure that these sources are clean, efficient and their use evidence-based.

[1] http://www.isonomia.co.uk/?p=3501

Banner photo: Composting (c) Zero Waste Europe

Note: The views and opinions expressed in this guest blog post are those of the author and not necessarily supported by BirdLife Europe/EEB/T&E.

Although most bioenergy is produced by burning agricultural and forestry biomass, it is also generated by burning the organic parts of municipal solid waste, biowaste or urban biomass. This includes food waste from restaurants, households, farmers markets, gardens, textiles, clothing, paper and other materials of organic origin. But have you ever tried to fuel a bonfire with a salad? Probably not, so this may not be the most efficient use of urban biowaste.

Although most bioenergy is produced by burning agricultural and forestry biomass, it is also generated by burning the organic parts of municipal solid waste, biowaste or urban biomass. This includes food waste from restaurants, households, farmers markets, gardens, textiles, clothing, paper and other materials of organic origin. But have you ever tried to fuel a bonfire with a salad? Probably not, so this may not be the most efficient use of urban biowaste.