Why is the global waste crisis a social justice issue?

World Day of Social Justice has been celebrated by the United Nations on February 20th every year. There is a good reason for that, as social justice strives for the impartial share of social, environmental, and economic advantages and disadvantages. The world’s most vulnerable communities continue to experience differential access to rights and opportunities, and disproportionately suffer more from environmental burdens, such as inadequate waste management and its subsequent repercussions.

What is environmental justice, and how is it connected to social justice?

Justice for all humans and the planet are not separate conversations but remain deeply linked. Human activity profoundly impacts the environment, as the environment continually influences our lives.

As an integral part of social justice, environmental justice addresses discrimination: waste disposal, resource extraction, and other activities that result in environmental degradation and impact the most vulnerable communities. The overwhelming majority of incinerators, dumps, landfills, and burn facilities are located near low-income communities, communities of colour, and marginalised communities. On a daily basis, residents deal with inadequate levels of noise, litter, increased vehicle traffic, smells, and air pollution. Emissions from incinerators lead to health-related issues due to overexposure to particles and dangerous pollutants, which also increase the risk of cardiac and respiratory disease, having the most impact on children and the elderly.

In some countries, wastepickers are the only form of solid waste collection, providing countless benefits such as high recycling rates, public health and safety, and environmental sustainability. Yet, wastepickers continue to be highly unprotected, working in unsafe and unhealthy conditions.

For decades, the environmental and social justice movement has strived to highlight the challenges borne by unprivileged communities, aiming to restore the unequal distribution of environmental benefits (such as access to nature, green spaces, clean air and water, landscape improvements) and disadvantages (risks of hazards from industrial, transport-generated and municipal pollution, etc.).

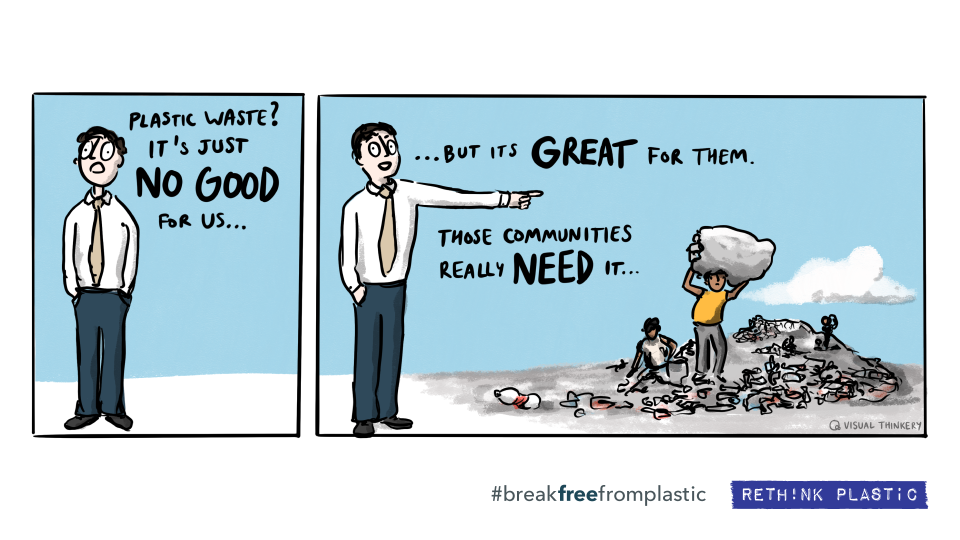

In this way, social and environmental justice both draw attention to power issues: who causes the pollution/waste and who suffers from it? And so, environmental rights lie at the intersection between human rights and environmental protection.

The global waste crisis rooted in toxic colonialism

In Europe today, a high percentage of waste is still incinerated or thrown in landfills; and in 2019, the EU exported a monthly average of 150,000 tonnes of plastic waste beyond its borders. However, there is a high discrepancy between the sheer scale of plastic waste trade and the ability of importing countries to deal with the waste responsibly. As an example, Malaysia has an installed recycling capacity of 515,009 tonnes but now imports on average 835,000 tonnes of plastic waste each year. In Indonesia, less than half of the country’s waste is adequately processed, while the rest is thrown in open-dumping landfills.

The global waste trade sharpens environmental inequality, hierarchy, exploitation along the lines of class and race on a global scale because the ones who suffer the negative impacts are the vulnerable communities who didn’t produce the waste. The issue of waste trade is, undoubtedly, an issue of colonialism.

The toxic and hazardous waste imported to the Global South mainly includes electronic, chemical and plastic waste, which is managed without any protection gear whatsoever, exposing workers through direct contact, inhalation, and more. Every year, about 50 million tons of e-waste are produced. While the majority comes from the United States and Europe, most of it is shipped to the Global South to be processed. If not done properly, e-waste leaks heavy metals, toxins and chemicals, thus polluting drinkable water, soil, and food crops.

Incinerated waste contributes to the release of various hazardous gases, heavy metals, and sulphur dioxide in the air, poisoning wildlife and local communities, who increasingly suffer from cancer, diabetes, hormone disruption, skin alteration, neurotoxicity, kidney, liver and reproductive damage, bone disease, and more.

When countries have no ability to process plastic trash, it often ends up in the oceans. Consumed by hundreds of aquatic species and large mammals alike, it kills millions of animals every year by entanglement or starvation. When plastic waste is not recyclable, it is often sent to illegal recycling factories that dispose of it by burying or burning it, affecting the health of those living nearby.

What’s next?

- To heal the systemic inequalities and institutional racism inherent to the waste crisis, it is crucial to allow those on the frontline of environmental justice’s struggles to hold a central role in creating zero waste communities. Wastepickers should be protected and acknowledged.

- The Global North should take responsibility for its waste and a complete ban on waste exports outside the EU should be implemented.

- Corporations must take full responsibility for their products by making Extended Producer Responsibility a mandatory practice; prioritising redesign and waste prevention; and setting up systems that make the disposal of waste redundant.

Alexia Dreau is a volunteer for Zero Waste Europe.